Proper 15A

Leftovers for all!

Matthew 15.21-28

Once upon a time, a woman called the local vicar and asked him if he would officiate at a funeral for her dog. ... The priest was a bit put off by the request, and with a somewhat disgusted tone in his voice, he suggested that there was no way he could do such a thing, and that she might try one of the other churches in the area. She agreed to do that but not before she asked the priest for some advice. "Do you think £500 is an appropriate honorarium for a funeral of this kind? she asked, and should I make the cheque out to the minister or to the church?" The priest quickly cleared his throat and said, "Wait a minute, why didn't you tell me your dog was Church of England."

That’s the only laugh you’re going to get out of me this morning. What a text to come back from holiday to! I wanted something straightforward to ease me back into the preaching task. And what have we got? “It’s not right to take bread out of children’s mouths and throw it to dogs.” Be clear just how severe these words from Jesus’ mouth are. Perhaps that's why the lectionary compilers suggest it be used as part of a longer passage, it doesn't seem quite so hard then. The hurt is in the word “dog.”

“Man’s best friend” we say. We sentimentalise and befriend dogs in ways that are peculiarly modern and western. I think you will only find dogs referred to positively in one place in scripture and that’s in the book of Tobit—when did you last hear that in church? Every other reference portrays them as scavenging curs.

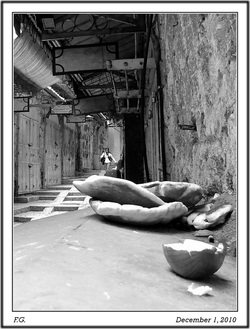

The point is easily seen in any African country. Yes, there are plenty of dogs, running loose. Almost all of them scrawny and roaming about sifting and sniffing through rubbish, and on the look out for food to steal. These dogs walk among the children playing in the street, it’s obvious that they are not the personal possession of any of them. They are just kind of there ... and for the most part they are barely tolerated and or ignored. Mothers who have little enough to feed their children don’t toss sausages and crusts to Fido.

In the land where Jesus lived, dogs carried about the same social standing as many of their counterparts anywhere in Africa today. Remember when Jesus tells the parable of "The Rich Man and Lazarus," Lazarus lays helpless at the gate, and Jesus gave us that gruesome little detail about the dogs that would come and lick his sores, well, that’s about it in terms of the way dogs were regarded.

That’s the kind of worldview from which Jesus makes his comment to the Gentile woman in our Gospel this morning. She asks for him to bring healing to her daughter and he says, "I was sent only to the lost sheep of Israel... It isn't right to take the children's food and throw it to the dogs." A prophet ministering outside the boundaries of Israel is like a mother who would deny food to her children and feed it to stray dogs instead. There’s no way you can make that a comfortable remark. I know lots of people have tried—they’ve said he was testing her faith; that he was stretching her courage in way that was good for her. But I think not. Why not hear it simply as it is?

Certainly such harsh words aren’t what we expect from Jesus. The analogy he uses doesn’t reflect the inclusiveness that we believe is part and parcel of his understanding of God and the world. This Jesus who, most of the time, we find welcoming sinners and tax collectors, touching lepers, and associating with people other people wouldn’t even give the time of day—here says something that is harsh, discriminatory and insulting. Yes, Jesus was a person of his time—a first-century Jew born into a world of boundaries, discrimination and exclusion. It’s so easy to idealise him in a completely unrealistic way. He was a person of his time. That’s what being a person is—it goes with the territory of incarnation.

Matthew lets us see that Jesus is human. This is a Jesus who learns and develops—like any of us. This is a Jesus who has to respond to what goes on around him—like any of us. This is a Jesus who doesn’t know everything—like any of us. This is a Jesus who is genuinely human.

But look at the nature of his humanity. Most of us, most of the time, let our personal prejudices, our personal likes and dislikes, rule our responses. It’s hard to step aside from those things and see some new possibility outside our own frames of reference. We have to be cajoled and persuaded into the effort. The truth of that is easily seen in the disciples’ reaction. To them the woman is clearly beyond the bounds; a nuisance they want to be rid of. Like the insistent beggar on the city corner who tries and tries to stop you walking on—what a nuisance.

Jesus does the other thing. He actually lets the nuisance engage him. This brave woman comes back at him powerfully. Even the analogy is better than his: ‘even the dogs,’ she says, ‘eat the crumbs that fall from the table.’ And in the encounter Jesus changes—that’s what human’s are really good at when they are brave enough to chance it. The woman teaches Jesus something new about the Kingdom—she widens its inclusion to be genuinely inclusive. And Jesus realises the truth of it: ‘Woman, great is your faith!’

Somebody said, the day you can no longer change is the day you stop being a human being. Well, Jesus is a human being, and this day he changes. His outlook, his worldview we might call it now, is lifted to something new. Let Jesus be our exemplar: we must dare to let our outlooks be changed too. We must dare to truly engage with the world and let life’s encounters work with what we know of God and so shape our living and understanding. According to Matthew the gospel writer in this difficult story, that is a Jesus thing to do.

A brave and faithful woman challenges Jesus, and he discovers, and we discover too, that it doesn’t matter whether you’re a Canaanite from Tyre or Sidon or anywhere else. All those boundaries and barriers we make so much of: ethnicity, class, nationality, upbringing—so many barriers, so many divisions—none of them matter. What matters is the person before God—every single person. As St Paul puts it, there is no longer Jew or Gentile, slave or free, male or female. The 'dividing wall of hostility' is broken down in Christ. It’s hard to think of God’s grace as leftovers, but isn’t that what this story says? There are enough leftovers for ALL.

That’s the only laugh you’re going to get out of me this morning. What a text to come back from holiday to! I wanted something straightforward to ease me back into the preaching task. And what have we got? “It’s not right to take bread out of children’s mouths and throw it to dogs.” Be clear just how severe these words from Jesus’ mouth are. Perhaps that's why the lectionary compilers suggest it be used as part of a longer passage, it doesn't seem quite so hard then. The hurt is in the word “dog.”

“Man’s best friend” we say. We sentimentalise and befriend dogs in ways that are peculiarly modern and western. I think you will only find dogs referred to positively in one place in scripture and that’s in the book of Tobit—when did you last hear that in church? Every other reference portrays them as scavenging curs.

The point is easily seen in any African country. Yes, there are plenty of dogs, running loose. Almost all of them scrawny and roaming about sifting and sniffing through rubbish, and on the look out for food to steal. These dogs walk among the children playing in the street, it’s obvious that they are not the personal possession of any of them. They are just kind of there ... and for the most part they are barely tolerated and or ignored. Mothers who have little enough to feed their children don’t toss sausages and crusts to Fido.

In the land where Jesus lived, dogs carried about the same social standing as many of their counterparts anywhere in Africa today. Remember when Jesus tells the parable of "The Rich Man and Lazarus," Lazarus lays helpless at the gate, and Jesus gave us that gruesome little detail about the dogs that would come and lick his sores, well, that’s about it in terms of the way dogs were regarded.

That’s the kind of worldview from which Jesus makes his comment to the Gentile woman in our Gospel this morning. She asks for him to bring healing to her daughter and he says, "I was sent only to the lost sheep of Israel... It isn't right to take the children's food and throw it to the dogs." A prophet ministering outside the boundaries of Israel is like a mother who would deny food to her children and feed it to stray dogs instead. There’s no way you can make that a comfortable remark. I know lots of people have tried—they’ve said he was testing her faith; that he was stretching her courage in way that was good for her. But I think not. Why not hear it simply as it is?

Certainly such harsh words aren’t what we expect from Jesus. The analogy he uses doesn’t reflect the inclusiveness that we believe is part and parcel of his understanding of God and the world. This Jesus who, most of the time, we find welcoming sinners and tax collectors, touching lepers, and associating with people other people wouldn’t even give the time of day—here says something that is harsh, discriminatory and insulting. Yes, Jesus was a person of his time—a first-century Jew born into a world of boundaries, discrimination and exclusion. It’s so easy to idealise him in a completely unrealistic way. He was a person of his time. That’s what being a person is—it goes with the territory of incarnation.

Matthew lets us see that Jesus is human. This is a Jesus who learns and develops—like any of us. This is a Jesus who has to respond to what goes on around him—like any of us. This is a Jesus who doesn’t know everything—like any of us. This is a Jesus who is genuinely human.

But look at the nature of his humanity. Most of us, most of the time, let our personal prejudices, our personal likes and dislikes, rule our responses. It’s hard to step aside from those things and see some new possibility outside our own frames of reference. We have to be cajoled and persuaded into the effort. The truth of that is easily seen in the disciples’ reaction. To them the woman is clearly beyond the bounds; a nuisance they want to be rid of. Like the insistent beggar on the city corner who tries and tries to stop you walking on—what a nuisance.

Jesus does the other thing. He actually lets the nuisance engage him. This brave woman comes back at him powerfully. Even the analogy is better than his: ‘even the dogs,’ she says, ‘eat the crumbs that fall from the table.’ And in the encounter Jesus changes—that’s what human’s are really good at when they are brave enough to chance it. The woman teaches Jesus something new about the Kingdom—she widens its inclusion to be genuinely inclusive. And Jesus realises the truth of it: ‘Woman, great is your faith!’

Somebody said, the day you can no longer change is the day you stop being a human being. Well, Jesus is a human being, and this day he changes. His outlook, his worldview we might call it now, is lifted to something new. Let Jesus be our exemplar: we must dare to let our outlooks be changed too. We must dare to truly engage with the world and let life’s encounters work with what we know of God and so shape our living and understanding. According to Matthew the gospel writer in this difficult story, that is a Jesus thing to do.

A brave and faithful woman challenges Jesus, and he discovers, and we discover too, that it doesn’t matter whether you’re a Canaanite from Tyre or Sidon or anywhere else. All those boundaries and barriers we make so much of: ethnicity, class, nationality, upbringing—so many barriers, so many divisions—none of them matter. What matters is the person before God—every single person. As St Paul puts it, there is no longer Jew or Gentile, slave or free, male or female. The 'dividing wall of hostility' is broken down in Christ. It’s hard to think of God’s grace as leftovers, but isn’t that what this story says? There are enough leftovers for ALL.