First Sunday of Advent (Year B)

Mark 13.24-37 Christ the Harlequin? (a homily)

In medieval times there was a holiday called the Feast of Fools, often around January 1st. Pious priests and serious tradespeople donned masks, sang outrageous ditties, and kept the whole world awake with revelry and satire. Minor clerics painted their faces and walked about in bishop’s robes and mocked the stately rituals of church and royal court. Sometimes a Lord of Misrule, a mock King or boy Bishop was elected to preside over the events. Boy Bishop’s sometimes even parodied the mass – no custom or convention was immune to ridicule and even the highest personages of the realm could expect to be lampooned.

The High-ups, as my Gran called them, I’m sure you understand what she meant, didn’t like the Feast of Fools, it was repeatedly condemned and criticized, indeed outrightly condemned by the Council of Basel in 1431, but the people took no notice, and the Feast of Fools survived until the 16thcentury. The Reformation and the Counter-Reformation finally killed it off – it just survives in the pranks of Halloween and New Year’s eve.

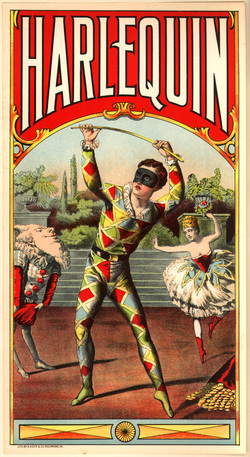

As that tradition died another arose – The Harlequin, the clown with the diamonds of variegated colour. The Harlequin came out of the 6th century Italian commedia dell’arte, the improvised popular comedy that took common everyday kind of stories and dialogue, and linked them to topical issues in a way that lifted people’s spirits, made them laugh, allowed them to see the absurd side of things, steeled them with a vision of mirth that could lift them above the horrors and hurts of life. The Harlequin enables us to laugh at life – not the laughter of scorn, no, this is the laughter that looks life squarely in the face and draws the sting of its hurts by seeing the hilarity in it, the absurdity, the pomposity of evil, the over-weaning arrogance of power, and the joy that is the foundation of life. The psalmist says God himself laughs at the wicked because he foresees their downfall. For the foolishness of God is wiser than people, and the weakness of God stronger than human wisdom.

Mark’s gospel today challenges us with stern words about the end, when even the powers of heaven are shaken. This is the Advent theme through the centuries of the church – the reality of evil, the crushing certainty of death, the horrors of human history, the terrifying violence and hardness in the hearts of people, the profound fear of what might yet be on the basis of what we know has already been. Keep alert, says Jesus in this passage, keep alert to the realities of the world. But we can hardly raise our heads, the horrors are too much, how do you keep alert, and stay sane. How do you sleep easy after seeing the horrors of the world on the TV in the corner? Lighten our darkness! we cry.

Enter onto our human stage, Christ the harlequin, to lift the pain and make life bearable – to awaken us to reality and yet give us a joyful hope. Don’t think the picture a new one – something a strange cleric has dreamed up, far from it. One of the very earliest representations of Christ in Christian art depicts a crucified human figure with the head of an ass. No one is sure what it means. Is it an arcane sign or a cruel parody? Either might be the case, or perhaps those catacomb Christians who drew it had a deeper sense of the comic absurdity of their position than we usually think. A wretched band of slaves, and derelicts, and powerless women – square pegs alright. Maybe they sensed how ludicrous their claims appeared. They knew they were fools for Christ, but they claimed that the foolishness of God is wiser than all the wisdom of humanity.

In the gospels there are hints in a similar direction. Like the jester, Christ defies custom and scorns the powerful and royal. Like a wandering troubadour, he has no place to lay his head. Like the clown in the circus parade, he satires earthly

authority by riding into Jerusalem replete with regal pageantry but no earthly power. Like a minstrel, he frequents the eating places of the common people and the parties of the disreputable. At the end he is costumed by his enemies in a

mocking caricature of royal paraphernalia. He is crucified amidst sniggers and taunts, with a sign over his head that lampoons his laughable claim. Keep alert, see life as it really is.

Christ the Harlequin – in a world of hurt and harm and tension and terror – what is he? Well, many things. The butt of our own fears and insecurities. The mirror to our own absurdities, allowing us to see ourselves in a way we find so hard to admit. The rebel who offers us the chance to break out of the cage of physical limits and social proprieties. The harlequin Christ is all these and more. He is constantly defeated, tricked, humiliated and trampled on. He is infinitely vulnerable, but never finally defeated – he brings light to our darkness.

Dante reports that when he finally arrived in Paradise after his arduous climb from the Inferno, he heard the choirs of angels singing praises to the Trinity and, he says, “It seemed like the laughter of the universe.” According to Dante, in hell

there is no hope and no laughter; in purgatory, there is no laughter but there is hope, whereas in heaven, hope is no longer necessary and laughter reigns.

The Harlequin, the Redeemer, calls us on.

The High-ups, as my Gran called them, I’m sure you understand what she meant, didn’t like the Feast of Fools, it was repeatedly condemned and criticized, indeed outrightly condemned by the Council of Basel in 1431, but the people took no notice, and the Feast of Fools survived until the 16thcentury. The Reformation and the Counter-Reformation finally killed it off – it just survives in the pranks of Halloween and New Year’s eve.

As that tradition died another arose – The Harlequin, the clown with the diamonds of variegated colour. The Harlequin came out of the 6th century Italian commedia dell’arte, the improvised popular comedy that took common everyday kind of stories and dialogue, and linked them to topical issues in a way that lifted people’s spirits, made them laugh, allowed them to see the absurd side of things, steeled them with a vision of mirth that could lift them above the horrors and hurts of life. The Harlequin enables us to laugh at life – not the laughter of scorn, no, this is the laughter that looks life squarely in the face and draws the sting of its hurts by seeing the hilarity in it, the absurdity, the pomposity of evil, the over-weaning arrogance of power, and the joy that is the foundation of life. The psalmist says God himself laughs at the wicked because he foresees their downfall. For the foolishness of God is wiser than people, and the weakness of God stronger than human wisdom.

Mark’s gospel today challenges us with stern words about the end, when even the powers of heaven are shaken. This is the Advent theme through the centuries of the church – the reality of evil, the crushing certainty of death, the horrors of human history, the terrifying violence and hardness in the hearts of people, the profound fear of what might yet be on the basis of what we know has already been. Keep alert, says Jesus in this passage, keep alert to the realities of the world. But we can hardly raise our heads, the horrors are too much, how do you keep alert, and stay sane. How do you sleep easy after seeing the horrors of the world on the TV in the corner? Lighten our darkness! we cry.

Enter onto our human stage, Christ the harlequin, to lift the pain and make life bearable – to awaken us to reality and yet give us a joyful hope. Don’t think the picture a new one – something a strange cleric has dreamed up, far from it. One of the very earliest representations of Christ in Christian art depicts a crucified human figure with the head of an ass. No one is sure what it means. Is it an arcane sign or a cruel parody? Either might be the case, or perhaps those catacomb Christians who drew it had a deeper sense of the comic absurdity of their position than we usually think. A wretched band of slaves, and derelicts, and powerless women – square pegs alright. Maybe they sensed how ludicrous their claims appeared. They knew they were fools for Christ, but they claimed that the foolishness of God is wiser than all the wisdom of humanity.

In the gospels there are hints in a similar direction. Like the jester, Christ defies custom and scorns the powerful and royal. Like a wandering troubadour, he has no place to lay his head. Like the clown in the circus parade, he satires earthly

authority by riding into Jerusalem replete with regal pageantry but no earthly power. Like a minstrel, he frequents the eating places of the common people and the parties of the disreputable. At the end he is costumed by his enemies in a

mocking caricature of royal paraphernalia. He is crucified amidst sniggers and taunts, with a sign over his head that lampoons his laughable claim. Keep alert, see life as it really is.

Christ the Harlequin – in a world of hurt and harm and tension and terror – what is he? Well, many things. The butt of our own fears and insecurities. The mirror to our own absurdities, allowing us to see ourselves in a way we find so hard to admit. The rebel who offers us the chance to break out of the cage of physical limits and social proprieties. The harlequin Christ is all these and more. He is constantly defeated, tricked, humiliated and trampled on. He is infinitely vulnerable, but never finally defeated – he brings light to our darkness.

Dante reports that when he finally arrived in Paradise after his arduous climb from the Inferno, he heard the choirs of angels singing praises to the Trinity and, he says, “It seemed like the laughter of the universe.” According to Dante, in hell

there is no hope and no laughter; in purgatory, there is no laughter but there is hope, whereas in heaven, hope is no longer necessary and laughter reigns.

The Harlequin, the Redeemer, calls us on.