Finding a discourse for living

Proper 5C

1 Kings 17.17-24; Luke 7.11-17

This story, which is unique to Luke’s Gospel, is often interpreted through the way it closely mirrors Elijah’s raising of the widow’s son at Zarephath (1 Kings 17.17-24) – surely the way to understand it suggested by today’s ordering of our readings. Here the focus is on the authority of the person through whom the miracle is achieved. Elijah as a ‘man of God’ has direct access to God’s power over life and death. In his exercising of that power the widow is convinced that God is at work in her home

(1 Kgs. 17.24).

Similarly, Jesus’ intervention at the town gate of Nain alerts a large crowd to the fact that ‘a great prophet’ who also has power over life and death is at work amongst them (Lk. 7.16). Of course, the discussion may well be extended into what Luke means by this close association of Elijah and Jesus, but that does not detract from the essential point that these miracles indicate God’s real and present action.

That’s one way into this miracle story, but I want to take another route. I want to ask the question ‘What’s being said to

the fledgling church by the way Luke tells the story? And therefore what is being said to us their successors?’ And I think a little psychological theory can really help.

A psychologically aware interpretation places the focus of the Lucan story in a rather different place than the perspective that dwells on the authority figure who is the agent of restored life. The reader is told that the deceased ‘was his mother’s only son’; that she was ‘a widow’; that Jesus had ‘compassion for her’; and that Jesus ‘gave’ the restored son ‘to his mother’. The concern of Jesus is principally for the woman rather than the deceased, and the intended focus of attention may well be on her needs rather than a substantiation of divine power. Analysis of the discourses in the story can

provide a way of understanding those needs and how Jesus meets them.

Undoubtedly compassion for a person recently bereaved is a feature of Jesus’ concern, nevertheless the Gospel writer

offers no explicit evidence of this beyond what is implied by the story’s substance. Instead the incident is couched in terms of the discourse now closed to the women through the death of her only close male relative and the way a new

discourse is opened by Jesus.

The social location of a widow is of foremost concern in the way the story develops: it all takes place in front of a

large crowd; Jesus addresses her directly though there is no indication that he knows her (ignoring usual social convention); rules about impurity are flouted (Jesus touches the dead man’s bier); and the once dead speaks, thus giving the widow a public voice that his death had taken from her (generally respectable women’s access to public discourse was through a prior relationship with a male member of the household). This restoration of voice is Jesus’ gift (v.15) and

its occurrence is voiced throughout the district and beyond (v.17). That spreading of the word, however, is not prompted by celebration but fear (v.16). It seems to me that there is a discourse of death and a discourse of life at play here. Let me explain.

Discourse analysis examines the way that language constructs how we experience life (Watts, Nye and Savage, 2002, p.

217). Rather than assuming language simply reflects the way things are, discourse analysis posits that language builds social reality. The analyst looks at the language employed and the ways that it is used and seeks to discover what

that usage says about the world and the subjects’ place within it.

Typically the analyst will look for patterns of emphasis, ways of thinking, recurrent concepts and words, unvoiced

assumptions behind expressions, things that go unnoticed or unremarked on, and other aspects of a group’s ways of expression that makes some things ‘self-evident’ and other things more difficult to even mention. Discourses ‘create and maintain distinctive social identities’ (Watts et al, p. 217), and are therefore a key feature of an individual’s sense of belonging within a group and also of a group’s location within wider society. In other words, the way things are voiced produces a particular way of living and being.

As a consequence of the death of her only son, the widow from Nain finds herself facing the prospective of discourse so

restricted as to render her effectively silent. As a woman her access to the speaking world was through her male kin –in this case her only son – but now he’s gone there is no one to speak for her and she cannot assume that she can speak for herself. The Hebrew word most often used to translate ‘widow’ (almana) has connotations of voicelessness or silence (Malina and Rohrbaugh, 2003, p. 423) as well as a sense of being forsaken and bound in grief. As ‘a silent one’(and at no point in the story does she speak) the widow is entering a fragile life of incredible vulnerability. Her sonless widowhood is likely to reduce her very life expectancy. Silence – both literally and metaphorically – is deathly.

When Jesus gives the widow back her son, alive again, he is also raising her from social death to life. But the discourse to which he is admitting her is not simply her old social position restored. Jesus has flouted the conventions of that discourse,

as the large crowd has seen – he has spoken to her when shouldn’t have, and he has made himself impure by his touching of the stretcher with the dead on it. At his point there is no way back to the old ways of talking about things.

Jesus is bringing her into the new ‘Jesus people discourse’ that recognizes him as Lord (v.13) and declares that the time of fulfilment has arrived (v.16b). In Luke’s community the place of the widow is assured and honoured (Acts 9.41), and his gospel underlines that some of the first to experience the liberating word were widows. This is part of the distinctive Christian discourse Luke is teaching his readers. This is a discipleship imperative for every age, since the word that has to be spread (v.17), although some only mention it out of fear. Summoning up all the courage we can, where can we speak in a new way, a Jesus way, which liberates people?

Readers are left to hear for themselves what the new voice of the widow will sound like. We might imagine Luke’s earliest readers listening intently to the voices of the widows amongst them. What is clear is that Jesus overturns the discourse of exclusion that was the widow’s lot. His voice re-shapes her experience and gives her entry to a new social world where the old conventions no longer have power. Again an agenda for a discipleship ready to challenge the status quo is disclosed in those things. Where and how do we support voices that are re-shaping life in a godly way?

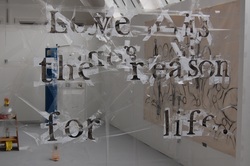

The story tells us that ‘giving voice’ so that a person can be part of a Jesus determined social world is an essential

part both of discipleship and ministerial practice. The psychological understanding of how discourses shape the worlds in which we live alerts us to the power of language and language used as power. It requires us as people of faith to take care in the words we use and the way we use them. It demands that the rhetoric of our speech be committed, responsible and liberating. As the preacher David Buttrick wrote, ‘Words do not create the world – only God creates with a Word – but language does constitute the world-in-consciousness, the significant social world in which we live. ... ... With words, we name the world (Buttrick, 1987, p. 9). The measure of that metaphorical power is Christ alone. Our task is to shape the

world – literally – with Godly words.

Books used:

Buttrick, David. (1987). Homiletic: Moves and Structures. London: SCM Press.

Malina, Bruce J., and Rohrbaugh, Richard L. (2003). Social-Science Commentary on the Synoptic Gospels. Minneapolis:

Fortress Press.

Savage, Sara and Boy-Macmillan, Eolene. (2007). The Human Face of the Church. Norwich: Canterbury Press.

Watts, Fraser, Nye, Rebecca and Savage, Sara. (2002). Psychology for Christian Ministry. London: Routledge.

(1 Kgs. 17.24).

Similarly, Jesus’ intervention at the town gate of Nain alerts a large crowd to the fact that ‘a great prophet’ who also has power over life and death is at work amongst them (Lk. 7.16). Of course, the discussion may well be extended into what Luke means by this close association of Elijah and Jesus, but that does not detract from the essential point that these miracles indicate God’s real and present action.

That’s one way into this miracle story, but I want to take another route. I want to ask the question ‘What’s being said to

the fledgling church by the way Luke tells the story? And therefore what is being said to us their successors?’ And I think a little psychological theory can really help.

A psychologically aware interpretation places the focus of the Lucan story in a rather different place than the perspective that dwells on the authority figure who is the agent of restored life. The reader is told that the deceased ‘was his mother’s only son’; that she was ‘a widow’; that Jesus had ‘compassion for her’; and that Jesus ‘gave’ the restored son ‘to his mother’. The concern of Jesus is principally for the woman rather than the deceased, and the intended focus of attention may well be on her needs rather than a substantiation of divine power. Analysis of the discourses in the story can

provide a way of understanding those needs and how Jesus meets them.

Undoubtedly compassion for a person recently bereaved is a feature of Jesus’ concern, nevertheless the Gospel writer

offers no explicit evidence of this beyond what is implied by the story’s substance. Instead the incident is couched in terms of the discourse now closed to the women through the death of her only close male relative and the way a new

discourse is opened by Jesus.

The social location of a widow is of foremost concern in the way the story develops: it all takes place in front of a

large crowd; Jesus addresses her directly though there is no indication that he knows her (ignoring usual social convention); rules about impurity are flouted (Jesus touches the dead man’s bier); and the once dead speaks, thus giving the widow a public voice that his death had taken from her (generally respectable women’s access to public discourse was through a prior relationship with a male member of the household). This restoration of voice is Jesus’ gift (v.15) and

its occurrence is voiced throughout the district and beyond (v.17). That spreading of the word, however, is not prompted by celebration but fear (v.16). It seems to me that there is a discourse of death and a discourse of life at play here. Let me explain.

Discourse analysis examines the way that language constructs how we experience life (Watts, Nye and Savage, 2002, p.

217). Rather than assuming language simply reflects the way things are, discourse analysis posits that language builds social reality. The analyst looks at the language employed and the ways that it is used and seeks to discover what

that usage says about the world and the subjects’ place within it.

Typically the analyst will look for patterns of emphasis, ways of thinking, recurrent concepts and words, unvoiced

assumptions behind expressions, things that go unnoticed or unremarked on, and other aspects of a group’s ways of expression that makes some things ‘self-evident’ and other things more difficult to even mention. Discourses ‘create and maintain distinctive social identities’ (Watts et al, p. 217), and are therefore a key feature of an individual’s sense of belonging within a group and also of a group’s location within wider society. In other words, the way things are voiced produces a particular way of living and being.

As a consequence of the death of her only son, the widow from Nain finds herself facing the prospective of discourse so

restricted as to render her effectively silent. As a woman her access to the speaking world was through her male kin –in this case her only son – but now he’s gone there is no one to speak for her and she cannot assume that she can speak for herself. The Hebrew word most often used to translate ‘widow’ (almana) has connotations of voicelessness or silence (Malina and Rohrbaugh, 2003, p. 423) as well as a sense of being forsaken and bound in grief. As ‘a silent one’(and at no point in the story does she speak) the widow is entering a fragile life of incredible vulnerability. Her sonless widowhood is likely to reduce her very life expectancy. Silence – both literally and metaphorically – is deathly.

When Jesus gives the widow back her son, alive again, he is also raising her from social death to life. But the discourse to which he is admitting her is not simply her old social position restored. Jesus has flouted the conventions of that discourse,

as the large crowd has seen – he has spoken to her when shouldn’t have, and he has made himself impure by his touching of the stretcher with the dead on it. At his point there is no way back to the old ways of talking about things.

Jesus is bringing her into the new ‘Jesus people discourse’ that recognizes him as Lord (v.13) and declares that the time of fulfilment has arrived (v.16b). In Luke’s community the place of the widow is assured and honoured (Acts 9.41), and his gospel underlines that some of the first to experience the liberating word were widows. This is part of the distinctive Christian discourse Luke is teaching his readers. This is a discipleship imperative for every age, since the word that has to be spread (v.17), although some only mention it out of fear. Summoning up all the courage we can, where can we speak in a new way, a Jesus way, which liberates people?

Readers are left to hear for themselves what the new voice of the widow will sound like. We might imagine Luke’s earliest readers listening intently to the voices of the widows amongst them. What is clear is that Jesus overturns the discourse of exclusion that was the widow’s lot. His voice re-shapes her experience and gives her entry to a new social world where the old conventions no longer have power. Again an agenda for a discipleship ready to challenge the status quo is disclosed in those things. Where and how do we support voices that are re-shaping life in a godly way?

The story tells us that ‘giving voice’ so that a person can be part of a Jesus determined social world is an essential

part both of discipleship and ministerial practice. The psychological understanding of how discourses shape the worlds in which we live alerts us to the power of language and language used as power. It requires us as people of faith to take care in the words we use and the way we use them. It demands that the rhetoric of our speech be committed, responsible and liberating. As the preacher David Buttrick wrote, ‘Words do not create the world – only God creates with a Word – but language does constitute the world-in-consciousness, the significant social world in which we live. ... ... With words, we name the world (Buttrick, 1987, p. 9). The measure of that metaphorical power is Christ alone. Our task is to shape the

world – literally – with Godly words.

Books used:

Buttrick, David. (1987). Homiletic: Moves and Structures. London: SCM Press.

Malina, Bruce J., and Rohrbaugh, Richard L. (2003). Social-Science Commentary on the Synoptic Gospels. Minneapolis:

Fortress Press.

Savage, Sara and Boy-Macmillan, Eolene. (2007). The Human Face of the Church. Norwich: Canterbury Press.

Watts, Fraser, Nye, Rebecca and Savage, Sara. (2002). Psychology for Christian Ministry. London: Routledge.