Reading out before reading in

Epiphany 4 (RCL)

Luke 4.21-30

My Grandfather was a staunch left-winger and consequently

he always read what was in his day the only Labour Party supported daily newspaper. After he died, my Grandma continued –out of loyalty and love – to have the same newspaper. The paper eventually went out of business and the title was bought by an international media mogul – the politics of the paper changed entirely and it often had about it a decidedly right-wing stance. Added to that, it now included ‘a page three girl’ – a picture of a usually topless young woman. My Grandma noticed none of this and continued as a daily subscriber until she died some twenty years later.

My Grandma ‘read in’ to the newspaper what she had experienced of it from her earlier years, and failed entirely to ‘read out’ from it its changed political and sexual stance. As strange as it seems she barely

noticed the naked form on page three – I didn’t once hear her refer to it!

Despite all the changes she got from the newspaper what she imagined it

contained rather than what it actually said: and this from an avid and

thoughtful reader, not a naive skimmer.

My Grandma and her newspaper illustrates well an issue Karl Barth, perhaps the greatest theologian of the twentieth-century, pointed to long ago. And that is the simple fact that no one can bring out the meaning of a text without at the same time adding something to it. He was worrying about getting to the truths of scripture honestly and sincerely, but the same worry applies to much more mundane texts. Sometimes, for example, advertising copywriters get it hilariously wrong and what many people read out from their

words is far from what they intended.

Grandma read into the paper a socialist colouring that was no longer there, and failed to read out what was actually being said. ‘Reading out’ and ‘reading in’ is something we all do, all of the time – though mostly, of course, entirely unconsciously. We read into things meanings that aren’t there, and we fail to read out what the author or editor

intended.

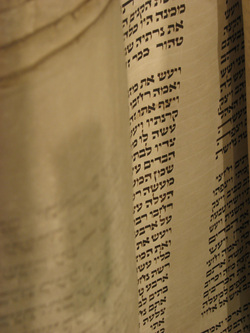

This tendency is something we need to be especially aware of as we think on the second part of this account of Jesus at the synagogue in the town of his upbringing – Nazareth. You’ll remember that he has read aloud words from the prophet Isaiah:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.

And then, sitting down, that is taking the seat of teaching authority, he says, ‘Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.’ That is that in his words and actions these words of the prophet are coming into reality; these signs of the messianic age are happening right now in the person of Jesus.

Now as you might imagine, this doesn’t go down well in this little town where he’s lived most of his life. Who does he think he is? What a cheek he’s got saying such a thing. We all know who he is; he is Joseph’s son, and his dad was rather better at wood turning and hinges than he is! What an upstart; what pomposity; what conceit.

It seems that Jesus had been expecting this reaction. He’d already done and said remarkable things in a town some miles away on the lake’s shore – although Luke doesn’t tell us what those things were. Jesus has anticipated that things won’t go as well in his hometown, and he quotes at them a proverb that has within it the sarcastic barb that he anticipates will fit

their response: ‘Doctor, cure yourself!’

And how right he is; the sarcasm mirrors precisely their rising anger at his affrontery. In hearing Luke’s account of the incident this is the point where we’ve got to be really careful about reading out of the story and not overly reading in.

Jesus quotes two precedents for his ministry – something the great Elijah did, and something his great successor Elisha did. Elijah saved the widow of Zarephath in a time of famine, and Elisha cured the Syrian officer Naaman of his leprosy. On both occasions there were many needy Jews suffering similarly, but these great men of Jewish faith chose to perform miracles for Gentiles. The implication being that the Nazarenes are refusing to recognise the action of God in Jesus because he’s too familiar to them – and the same could be said of what Elijah and Elisha did in these instances. It is as if Jesus is saying, ‘You are as dull to God’s saving action as were so many in the age of Elijah and Elisha. Foreigners could see what was happening but too many of their contemporaries could. And you are just like that unbelieving lot.’

Boy, did that suggestion make them angry. Some were for killing him there and then: ‘Over the edge of the cliff with him!’

Reading the story as Christians it’s all too easy to draw the wrong conclusion from this. The fury of the congregation in Nazareth that morning draws from us the urge to defend Jesus and condemn the Jewish faithful. We read too much into this incident and make it about ‘them’ instead of it being about us, all of us in our envy, jealousy, and urge to be on

top.

So this story is preached as an indication of the xenophobia of the Jews, or of a perverse ethnocentrism that made them

indifferent to others. But that is NOT what the incident tells us. We read in an antagonism towards the Jewish faith that simply isn’t there.

What prompts the anger of the congregation is the fact that they had not been included in the messianic blessings that he evidentially had distributed at Capernaum. Like Elijah and Elisha, the outpouring of such blessings has a particularity about it. That isn’t to say that God’s action is partial and prejudiced, but that humanity experiences God’s action in particular ways so that we may know it in the particularity that is part of our uniqueness as people. We want to be treated as particular, yet perversely we ourselves want to be treated as particular. God’s action in a particular place and amongst particular people shouldn’t be grounds for jealousy, recrimination, and envy, but too often it is, and it certainly was that morning in Nazareth.

This is an incident about the power of envy and jealousy to corrupt and blind people to God’s action. Don’t lay hands on Jesus and threaten him because his blessings seem to rest elsewhere and particularly. Instead rejoice and wait for the fruits of that particularity to bless you too, when the time is ripe.

Don’t read in a story of disbelieving Jews; rather read out a challenging word to us all: the Messiah’s blessings are indeed radically inclusive but that means they must be particular. Don’t be envious of Capernaum. Wait until you too may share the particular joy of the widow and the commander – their salvation is a sign to you of good things to come; never a fence that excludes you from the promise.

This scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing. That word once spoken will never be rescinded.

he always read what was in his day the only Labour Party supported daily newspaper. After he died, my Grandma continued –out of loyalty and love – to have the same newspaper. The paper eventually went out of business and the title was bought by an international media mogul – the politics of the paper changed entirely and it often had about it a decidedly right-wing stance. Added to that, it now included ‘a page three girl’ – a picture of a usually topless young woman. My Grandma noticed none of this and continued as a daily subscriber until she died some twenty years later.

My Grandma ‘read in’ to the newspaper what she had experienced of it from her earlier years, and failed entirely to ‘read out’ from it its changed political and sexual stance. As strange as it seems she barely

noticed the naked form on page three – I didn’t once hear her refer to it!

Despite all the changes she got from the newspaper what she imagined it

contained rather than what it actually said: and this from an avid and

thoughtful reader, not a naive skimmer.

My Grandma and her newspaper illustrates well an issue Karl Barth, perhaps the greatest theologian of the twentieth-century, pointed to long ago. And that is the simple fact that no one can bring out the meaning of a text without at the same time adding something to it. He was worrying about getting to the truths of scripture honestly and sincerely, but the same worry applies to much more mundane texts. Sometimes, for example, advertising copywriters get it hilariously wrong and what many people read out from their

words is far from what they intended.

Grandma read into the paper a socialist colouring that was no longer there, and failed to read out what was actually being said. ‘Reading out’ and ‘reading in’ is something we all do, all of the time – though mostly, of course, entirely unconsciously. We read into things meanings that aren’t there, and we fail to read out what the author or editor

intended.

This tendency is something we need to be especially aware of as we think on the second part of this account of Jesus at the synagogue in the town of his upbringing – Nazareth. You’ll remember that he has read aloud words from the prophet Isaiah:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.

And then, sitting down, that is taking the seat of teaching authority, he says, ‘Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.’ That is that in his words and actions these words of the prophet are coming into reality; these signs of the messianic age are happening right now in the person of Jesus.

Now as you might imagine, this doesn’t go down well in this little town where he’s lived most of his life. Who does he think he is? What a cheek he’s got saying such a thing. We all know who he is; he is Joseph’s son, and his dad was rather better at wood turning and hinges than he is! What an upstart; what pomposity; what conceit.

It seems that Jesus had been expecting this reaction. He’d already done and said remarkable things in a town some miles away on the lake’s shore – although Luke doesn’t tell us what those things were. Jesus has anticipated that things won’t go as well in his hometown, and he quotes at them a proverb that has within it the sarcastic barb that he anticipates will fit

their response: ‘Doctor, cure yourself!’

And how right he is; the sarcasm mirrors precisely their rising anger at his affrontery. In hearing Luke’s account of the incident this is the point where we’ve got to be really careful about reading out of the story and not overly reading in.

Jesus quotes two precedents for his ministry – something the great Elijah did, and something his great successor Elisha did. Elijah saved the widow of Zarephath in a time of famine, and Elisha cured the Syrian officer Naaman of his leprosy. On both occasions there were many needy Jews suffering similarly, but these great men of Jewish faith chose to perform miracles for Gentiles. The implication being that the Nazarenes are refusing to recognise the action of God in Jesus because he’s too familiar to them – and the same could be said of what Elijah and Elisha did in these instances. It is as if Jesus is saying, ‘You are as dull to God’s saving action as were so many in the age of Elijah and Elisha. Foreigners could see what was happening but too many of their contemporaries could. And you are just like that unbelieving lot.’

Boy, did that suggestion make them angry. Some were for killing him there and then: ‘Over the edge of the cliff with him!’

Reading the story as Christians it’s all too easy to draw the wrong conclusion from this. The fury of the congregation in Nazareth that morning draws from us the urge to defend Jesus and condemn the Jewish faithful. We read too much into this incident and make it about ‘them’ instead of it being about us, all of us in our envy, jealousy, and urge to be on

top.

So this story is preached as an indication of the xenophobia of the Jews, or of a perverse ethnocentrism that made them

indifferent to others. But that is NOT what the incident tells us. We read in an antagonism towards the Jewish faith that simply isn’t there.

What prompts the anger of the congregation is the fact that they had not been included in the messianic blessings that he evidentially had distributed at Capernaum. Like Elijah and Elisha, the outpouring of such blessings has a particularity about it. That isn’t to say that God’s action is partial and prejudiced, but that humanity experiences God’s action in particular ways so that we may know it in the particularity that is part of our uniqueness as people. We want to be treated as particular, yet perversely we ourselves want to be treated as particular. God’s action in a particular place and amongst particular people shouldn’t be grounds for jealousy, recrimination, and envy, but too often it is, and it certainly was that morning in Nazareth.

This is an incident about the power of envy and jealousy to corrupt and blind people to God’s action. Don’t lay hands on Jesus and threaten him because his blessings seem to rest elsewhere and particularly. Instead rejoice and wait for the fruits of that particularity to bless you too, when the time is ripe.

Don’t read in a story of disbelieving Jews; rather read out a challenging word to us all: the Messiah’s blessings are indeed radically inclusive but that means they must be particular. Don’t be envious of Capernaum. Wait until you too may share the particular joy of the widow and the commander – their salvation is a sign to you of good things to come; never a fence that excludes you from the promise.

This scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing. That word once spoken will never be rescinded.