Knowing what's good for you

Trinity 4 (Proper 8B)

Mark 5.21-43

How do you know what’s good for you? A little bit of what you fancy does you good, according to my Gran. She thought it referred to food though I think that originated in a musical hall song that suggested something altogether more raunchy! A little bit of what you fancy ... Echoed perhaps in that slogan they used years ago to sell cream cakes, naughty but nice!

These thoughts came to me on thinking about a recent advert for a well known chocolate hazelnut spread – you know that stuff that is very brown, very gooey, and sticks to the top of your mouth. Just lovely! But hardly a health food for the slimmer figure – 55% sugar and 30+% fat – yet that same wonderfully gooey stuff is currently being sold as one of a healthy fives vegetables day. Get a portion of veg by ladling chocolate spread on your toast – what a way to eat vegetables – beats celery every time! Yes, it’s part of a health conscious diet – after all there are fifty nuts in every pot. And also a nut at every table that believes that!

How do you know what’s good foryou?

Jairus thinks he knows what’s good for his little girl. Things are desperate. She’s at the point of death. Nobody has been able to do anything. There is this Holy Man – they say he has the healing touch, perhaps he could do what no one else has

managed? Jairus has heard that he is back in Jewish territory. He’ll go and find him.

Lots of other people have found him too. The place is swarming. There is no way Jairus can get a private word. This can’t be a private consultation. There is nothing for it but to push his way through the crowd. It is his daughter’s last chance and he’ll do anything. So he elbows his way to where Jesus is. Then he throws himself onto the dusty ground there in front of the holy man. The hubbub stops. Silence and stillness ripples through the crowd like a wave on the

lake.

‘That’s Jairus,’ somebody whispers.

‘He’s something big in their synagogue isn’t he?’

‘Yeah when there was all that kafuffle about the rebuild of the place he was the one who got it done, you know.’

‘Really?’

‘Yeah, without him it would still be just a heap of stones.’

‘Big fish, then!’

‘He’s the one who holds it all together – plenty of cash, you know; lot’s of clout.’

‘Why’s he on the dirt in front of him?’

‘Sh, sh ... he’s saying something.’

‘My little daughter is at the point of death. Come and lay your hands on her, so that she may be made well, and

live.’

What has it cost this man in dignity, in face, to throw himself there? And you know it has because of the way he addresses Jesus. He is direct in his speech – he asks for just what he wants. There’s no circumlocution as someone lower down the social scale would have had to speak. He makes his request as he would to someone of equal status to himself, but he does it from the floor! He could have sent a servant with a message. He could have insisted on a meeting behind closed doors. Instead he goes himself and throws himself at the teacher’s feet.

He’s made a judgement about what’s good for him, what’s good for his little girl. And that motivates him to do this extraordinary thing. He’s on the floor, he body pleading with Jesus for action, even if his words are still in the realm of man to man encounter between equals. And as he staggers to his feet, hemmed in by the onlookers, his tear-filled eyes urging Jesus after him. Nothing is said, but the whole lot moves those few steps in the direction of Jairus’ home. No word of encouragement is given, no reassuring order of decision. Just a step or two in the right direction – Jesus, Jairus, the whole crowd. Is his pleading meeting with the response he wants? Perhaps; perhaps not. Why doesn’t somebody say

something? ‘What’s going on?’ is the word in the crowd.

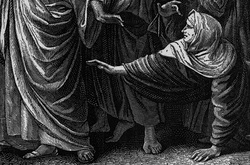

The attention is all on Jesus and Jairus. No one noticed a furtive figure gently pressing her way through the

crowd. Her head is down, her shoulders sloping, her face covered. She doesn’t want to be noticed for she knows if she is there will be shouts and taunts, maybe even stones. She’s a bleeding woman, not fit to be out in society. Nameless, alone. Contaminated, impure, whose impurity leaches out to infect those whom she touches. Socially a pariah. Nobody wants her anywhere near them. And it’s been like that for years. With the loss of blood has gone the loss of everything else; impoverished, blooded, ostracised, hungry, alienated, terrified.

She thinks she knows what’s good for her. ‘If I could just touch his clothes. Just a brushing of his hem with a finger tip, that’s all. If I could but glance my hand along the fabric, maybe that would be enough. Maybe that could change things.

Maybe that could help me. Maybe. Maybe.’

They’re all looking at Jairus. All thinking about what’s going to happen. All pressing on eager to see how it turns out.

Who has even seen her in the melee? She reaches out, jostled right and left by the press of the crowd. She

reaches out, her arm straining forward. And the tips of her fingers touch just the hem of his garment.

Go on. Do it. Run the tip of your fingers along the edge of his clothing. That’s all it was, but the lightest of touches.

Nothing more than a downy feather landing, the glancing touch of a leaf, the whisper of a breeze. But she knew in that instant that the ooze of warm, trickling blood had stopped. Her eyes closed in that moment of delight, relief. It’s too good to be true – but it is true! And then the awful reality dawns, it is not just the bleeding that has stopped, the crowd

has too.

There are hisses of derision. Gasps of anger. ‘What the hell is she doing here?’ Too many know her circumstances. News of the state of her body runs through the crowd like a fire. All are turned towards her. And in another instant as the mood of the crowd turns nasty, Jesus speaks. For the first time, Jesus speaks, ‘Who touched my clothes?’

As ever the disciples are the ones who don’t seem to know what’s going on, ‘Come off it boss, you see this lot pushing and shoving and you expect to know who touched you? You’re kidding.’ So often they’re such fools.

The crowd knows full well who touched him. And the nameless woman knows the crowd knows. And she knows what the consequence of that knowing is. She deliberately touched him, contaminated him, made her impurity his impurity. Even now people are shuffling back, making space. They don’t want it to spread. She’s gone too far. There will be

consequences. Does she see out of the corner of her eye someone reach down for a stone, and another pick up a

stick. Whatever use Jesus might have been to Jairus and to the crowd, he is of no use now. He’ll have to put himself through the purification ritual. Until he does so we want nothing more to do with him – anymore than we

want to have anything to do with her.

No wonder then that when she steps forward, she does so in fear and trembling. There will be consequences. Her touching him now seems rash, too much, too dangerous, too risky even given her despair. She falls on the dirt in front of him, sobbing out the truth – the whole truth, the whole sorry tale of her impurity, her despair, the blood and the anguish.

There are gasps of ‘Shame.’

‘Daughter’

What?

‘Daughter.’

He calls her daughter; he says you’re mine. You belong to this family – outcast no more – you are my daughter, you

belong. Your faith, your action in reaching out has made you well. You knew what was good for you. Be at peace – be afraid no longer, You are healed, daughter.

Another voice is heard – panting it out, he has run hard to get there.

‘Your daughter is dead.’

Does Jairus scream? Does he collapse to the floor again? Or does he just turn away, despondent? Mark doesn’t tell

us. What we do know is that his worse fears seem to have been confirmed. He had come in his despair thinking, hoping, longing, that he knew what was best for his daughter. But it has all turned to dust. Vital time wasted. The chance of healing thwarted by the woman’s intervention. The ordering of Jairus’universe threatened. The things of taboo and purity, and right behaviour just thrown aside. He had thought he knew what was best for his daughter, but it has come to nothing. Yet more is asked of him. Jesus moves off again towards his house.

‘Do not fear, only believe.’

Though others will laugh to scorn. Though the synagogue rules have been torn apart. Though your place in community is threatened. Though death rules in a house of wailing. Though your judgement looks now like folly. Though the jewel of a

father’s heart lies dead. ‘Do not fear, only believe.’

‘Talitha cum’

Little girl, little daughter, get up. As another has been declared a daughter, adopted and restored, though all around would have denied her; so this little one is restored as a daughter with all the promise a young life brings. And lest you should miss the point Mark tells us she was twelve years old – she is of an age when she will start bleeding. Her possibility of bleeding, of making life, has come through the adoption of one who has bled too much.

How do you know what’s good for you?

Jairus thought he knew. But it was so much more. The inclusion of the excluded, the creation of bonds of which he couldn’t have conceived, a belonging together that he would never have seen.

How do you know what’s good for you?

The woman thought she knew. But it was so much more. The ability to stand up for herself, even in fear and trembling, a new sense of worth, even more than she was expecting, incorporation – a daughter again.

Luther said the Bible has arms and legs and walks about amongst us. He knew what he was saying.

Are you Jairus, are you the woman, are you the crowd, are you the disciples? Are you sometimes one and sometimes the other?

Who needs to be included?

Who is on the margins unnoticed?

What is God saying to you, now?

How do you know what’s good for you?

These thoughts came to me on thinking about a recent advert for a well known chocolate hazelnut spread – you know that stuff that is very brown, very gooey, and sticks to the top of your mouth. Just lovely! But hardly a health food for the slimmer figure – 55% sugar and 30+% fat – yet that same wonderfully gooey stuff is currently being sold as one of a healthy fives vegetables day. Get a portion of veg by ladling chocolate spread on your toast – what a way to eat vegetables – beats celery every time! Yes, it’s part of a health conscious diet – after all there are fifty nuts in every pot. And also a nut at every table that believes that!

How do you know what’s good foryou?

Jairus thinks he knows what’s good for his little girl. Things are desperate. She’s at the point of death. Nobody has been able to do anything. There is this Holy Man – they say he has the healing touch, perhaps he could do what no one else has

managed? Jairus has heard that he is back in Jewish territory. He’ll go and find him.

Lots of other people have found him too. The place is swarming. There is no way Jairus can get a private word. This can’t be a private consultation. There is nothing for it but to push his way through the crowd. It is his daughter’s last chance and he’ll do anything. So he elbows his way to where Jesus is. Then he throws himself onto the dusty ground there in front of the holy man. The hubbub stops. Silence and stillness ripples through the crowd like a wave on the

lake.

‘That’s Jairus,’ somebody whispers.

‘He’s something big in their synagogue isn’t he?’

‘Yeah when there was all that kafuffle about the rebuild of the place he was the one who got it done, you know.’

‘Really?’

‘Yeah, without him it would still be just a heap of stones.’

‘Big fish, then!’

‘He’s the one who holds it all together – plenty of cash, you know; lot’s of clout.’

‘Why’s he on the dirt in front of him?’

‘Sh, sh ... he’s saying something.’

‘My little daughter is at the point of death. Come and lay your hands on her, so that she may be made well, and

live.’

What has it cost this man in dignity, in face, to throw himself there? And you know it has because of the way he addresses Jesus. He is direct in his speech – he asks for just what he wants. There’s no circumlocution as someone lower down the social scale would have had to speak. He makes his request as he would to someone of equal status to himself, but he does it from the floor! He could have sent a servant with a message. He could have insisted on a meeting behind closed doors. Instead he goes himself and throws himself at the teacher’s feet.

He’s made a judgement about what’s good for him, what’s good for his little girl. And that motivates him to do this extraordinary thing. He’s on the floor, he body pleading with Jesus for action, even if his words are still in the realm of man to man encounter between equals. And as he staggers to his feet, hemmed in by the onlookers, his tear-filled eyes urging Jesus after him. Nothing is said, but the whole lot moves those few steps in the direction of Jairus’ home. No word of encouragement is given, no reassuring order of decision. Just a step or two in the right direction – Jesus, Jairus, the whole crowd. Is his pleading meeting with the response he wants? Perhaps; perhaps not. Why doesn’t somebody say

something? ‘What’s going on?’ is the word in the crowd.

The attention is all on Jesus and Jairus. No one noticed a furtive figure gently pressing her way through the

crowd. Her head is down, her shoulders sloping, her face covered. She doesn’t want to be noticed for she knows if she is there will be shouts and taunts, maybe even stones. She’s a bleeding woman, not fit to be out in society. Nameless, alone. Contaminated, impure, whose impurity leaches out to infect those whom she touches. Socially a pariah. Nobody wants her anywhere near them. And it’s been like that for years. With the loss of blood has gone the loss of everything else; impoverished, blooded, ostracised, hungry, alienated, terrified.

She thinks she knows what’s good for her. ‘If I could just touch his clothes. Just a brushing of his hem with a finger tip, that’s all. If I could but glance my hand along the fabric, maybe that would be enough. Maybe that could change things.

Maybe that could help me. Maybe. Maybe.’

They’re all looking at Jairus. All thinking about what’s going to happen. All pressing on eager to see how it turns out.

Who has even seen her in the melee? She reaches out, jostled right and left by the press of the crowd. She

reaches out, her arm straining forward. And the tips of her fingers touch just the hem of his garment.

Go on. Do it. Run the tip of your fingers along the edge of his clothing. That’s all it was, but the lightest of touches.

Nothing more than a downy feather landing, the glancing touch of a leaf, the whisper of a breeze. But she knew in that instant that the ooze of warm, trickling blood had stopped. Her eyes closed in that moment of delight, relief. It’s too good to be true – but it is true! And then the awful reality dawns, it is not just the bleeding that has stopped, the crowd

has too.

There are hisses of derision. Gasps of anger. ‘What the hell is she doing here?’ Too many know her circumstances. News of the state of her body runs through the crowd like a fire. All are turned towards her. And in another instant as the mood of the crowd turns nasty, Jesus speaks. For the first time, Jesus speaks, ‘Who touched my clothes?’

As ever the disciples are the ones who don’t seem to know what’s going on, ‘Come off it boss, you see this lot pushing and shoving and you expect to know who touched you? You’re kidding.’ So often they’re such fools.

The crowd knows full well who touched him. And the nameless woman knows the crowd knows. And she knows what the consequence of that knowing is. She deliberately touched him, contaminated him, made her impurity his impurity. Even now people are shuffling back, making space. They don’t want it to spread. She’s gone too far. There will be

consequences. Does she see out of the corner of her eye someone reach down for a stone, and another pick up a

stick. Whatever use Jesus might have been to Jairus and to the crowd, he is of no use now. He’ll have to put himself through the purification ritual. Until he does so we want nothing more to do with him – anymore than we

want to have anything to do with her.

No wonder then that when she steps forward, she does so in fear and trembling. There will be consequences. Her touching him now seems rash, too much, too dangerous, too risky even given her despair. She falls on the dirt in front of him, sobbing out the truth – the whole truth, the whole sorry tale of her impurity, her despair, the blood and the anguish.

There are gasps of ‘Shame.’

‘Daughter’

What?

‘Daughter.’

He calls her daughter; he says you’re mine. You belong to this family – outcast no more – you are my daughter, you

belong. Your faith, your action in reaching out has made you well. You knew what was good for you. Be at peace – be afraid no longer, You are healed, daughter.

Another voice is heard – panting it out, he has run hard to get there.

‘Your daughter is dead.’

Does Jairus scream? Does he collapse to the floor again? Or does he just turn away, despondent? Mark doesn’t tell

us. What we do know is that his worse fears seem to have been confirmed. He had come in his despair thinking, hoping, longing, that he knew what was best for his daughter. But it has all turned to dust. Vital time wasted. The chance of healing thwarted by the woman’s intervention. The ordering of Jairus’universe threatened. The things of taboo and purity, and right behaviour just thrown aside. He had thought he knew what was best for his daughter, but it has come to nothing. Yet more is asked of him. Jesus moves off again towards his house.

‘Do not fear, only believe.’

Though others will laugh to scorn. Though the synagogue rules have been torn apart. Though your place in community is threatened. Though death rules in a house of wailing. Though your judgement looks now like folly. Though the jewel of a

father’s heart lies dead. ‘Do not fear, only believe.’

‘Talitha cum’

Little girl, little daughter, get up. As another has been declared a daughter, adopted and restored, though all around would have denied her; so this little one is restored as a daughter with all the promise a young life brings. And lest you should miss the point Mark tells us she was twelve years old – she is of an age when she will start bleeding. Her possibility of bleeding, of making life, has come through the adoption of one who has bled too much.

How do you know what’s good for you?

Jairus thought he knew. But it was so much more. The inclusion of the excluded, the creation of bonds of which he couldn’t have conceived, a belonging together that he would never have seen.

How do you know what’s good for you?

The woman thought she knew. But it was so much more. The ability to stand up for herself, even in fear and trembling, a new sense of worth, even more than she was expecting, incorporation – a daughter again.

Luther said the Bible has arms and legs and walks about amongst us. He knew what he was saying.

Are you Jairus, are you the woman, are you the crowd, are you the disciples? Are you sometimes one and sometimes the other?

Who needs to be included?

Who is on the margins unnoticed?

What is God saying to you, now?

How do you know what’s good for you?